So…what is sake?

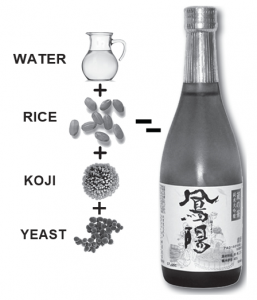

A lot of folks think that sake is rice wine. In fact, it’s not wine at all. If anything, it’s more closely related to beer, as it is actually brewed.

What is it made from exactly? Water, rice, yeast and koji…and sometimes alcohol…happily explained below.

RICES

There are 100 plus strains of sake rice, with maybe 25 of those in active use today. Those below are some of the most favored strains for top quality sake. Though each has distinctive characteristics, these are not as obvious and defining in sake as grape varieties are in wine. In fact, each type of rice can produce a myriad of different styles, aromas, and flavors. Additionally, many producers looking for further complexity and balance will use more than one type in a single sake.

A large majority of sake brewers consider Yamada Nishiki to be the best possible rice for brewing daiginjo, the highest grade of premium sake. It produces delicate, fragrant, feminine sake. Its ability to absorb water and dissolve quickly into the sake fermenting mash makes it a favorite amongst brewers. Hyogo is the most prolific region for Yamada Nishiki. A hybrid of yamadabo and wataribune, themselves virtually unused for decades, Yamada Nishiki is definitely a noble offspring of obscurity; now the most expensive of sake rices. 33.3% of the 2015 harvest.

A large majority of sake brewers consider Yamada Nishiki to be the best possible rice for brewing daiginjo, the highest grade of premium sake. It produces delicate, fragrant, feminine sake. Its ability to absorb water and dissolve quickly into the sake fermenting mash makes it a favorite amongst brewers. Hyogo is the most prolific region for Yamada Nishiki. A hybrid of yamadabo and wataribune, themselves virtually unused for decades, Yamada Nishiki is definitely a noble offspring of obscurity; now the most expensive of sake rices. 33.3% of the 2015 harvest.

Gohyakumangoku is the second most popular sake rice in Japan. All sake rice is planted later than table rice yet Gohyakumangoku can be harvested as early as mid-August, while Yamada Nishiki is typically not harvested until October. This rice is most commonly found growing along the northwestern coast of Japan, although the region of Niigata is often credited with putting this rice on the sake map. This rice produces a classic style of sake, clean, light, and refreshing. 24.7% of the 2015 harvest.

Gohyakumangoku is the second most popular sake rice in Japan. All sake rice is planted later than table rice yet Gohyakumangoku can be harvested as early as mid-August, while Yamada Nishiki is typically not harvested until October. This rice is most commonly found growing along the northwestern coast of Japan, although the region of Niigata is often credited with putting this rice on the sake map. This rice produces a classic style of sake, clean, light, and refreshing. 24.7% of the 2015 harvest.

Miyama Nishiki is widely used in northern Japan and is known for producing rich, full bodied sakes. Known for its prolific growth and resistance to cold weather, this rice is often used to create hybrid rice strains, 60 offspring and counting. 8.7% of the 2015 harvest.

Miyama Nishiki is widely used in northern Japan and is known for producing rich, full bodied sakes. Known for its prolific growth and resistance to cold weather, this rice is often used to create hybrid rice strains, 60 offspring and counting. 8.7% of the 2015 harvest.

Omachi is known for rich, earthy flavors that are some of the easiest to identify when tasting sake. Generally less fragrant, more defined by flavor elements, more earthiness. The individual flavor components compete against each other in a compellingly faceted way, as opposed to blending harmoniously, as they might with Yamada Nishiki. Originating in Okayama, Omachi may be the last pure strain of sake rice still in use in Japan. Growing quickly in popularity, demand outstripped the harvest in 2015.

Koshi Tanrei is a relatively recent hybrid used almost exclusively in Niigata Prefecture. Koshi Tanrei marries the parental qualities of Gohyakumangoku’s clean and dry style with Yamada Nishiki’s fragrant, floral characteristics and can be polished very far down. Brewers in Niigata have been working to use only local ingredients in their sakes, but because Yamada Nishiki is predominantly grown outside of Niigata, it was difficult until the development of Koshi Tanrei for these brewers to make daiginjo grade sakes using exclusively local rice. Bravo for them!

Koshi Tanrei is a relatively recent hybrid used almost exclusively in Niigata Prefecture. Koshi Tanrei marries the parental qualities of Gohyakumangoku’s clean and dry style with Yamada Nishiki’s fragrant, floral characteristics and can be polished very far down. Brewers in Niigata have been working to use only local ingredients in their sakes, but because Yamada Nishiki is predominantly grown outside of Niigata, it was difficult until the development of Koshi Tanrei for these brewers to make daiginjo grade sakes using exclusively local rice. Bravo for them!

(For further reading on rice and more, you will find no better expert than John Gauntner. Explore his wealth of knowledge at sake-world.com.)

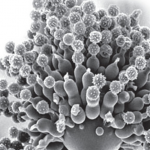

KOJI

Aspergillus oryzae, also known as koji-kin, is a filamentous fungus, a mold. The koji-kin fungus has been called Japan’s “national microorganism” because of its importance not only for making sake, but also for making other traditional foods, such as miso and soy sauce. I have Googled it; we do not have a “national microorganism”. We should urge our Administration to get on this before all the good ones are taken.

Koji is the steamed rice that has had the koji-kin mold spores cultivated onto it. Koji-kin creates several enzymes as it propagates in the Koji. There are many enzymes produced in this process. Some act to create fermentable sugar, others create sugars that will not ferment but instead affect texture and flavor in sake.

The koji-making process takes 40-45 hours in a room where temperature and humidity are strictly controlled. During this entire time the koji is frequently mixed; by hand for high quality sake. Rice type, pH and mineral content of the water, and a myriad of other details also influence the way koji is made. Koji is used at least four times throughout the process, each time it is made fresh and used immediately.

The koji-making process takes 40-45 hours in a room where temperature and humidity are strictly controlled. During this entire time the koji is frequently mixed; by hand for high quality sake. Rice type, pH and mineral content of the water, and a myriad of other details also influence the way koji is made. Koji is used at least four times throughout the process, each time it is made fresh and used immediately.