Frog’s Leap Part Two: The Iconic Label and Early Days of Organic Farming

The Frog’s Leap story, part two

To celebrate our kickoff of Frog’s Leap Winery at The Wine Company, we want to share their amazing story and history with our readers. If you have not yet read it, be sure to check out part one of their amazing story.

***

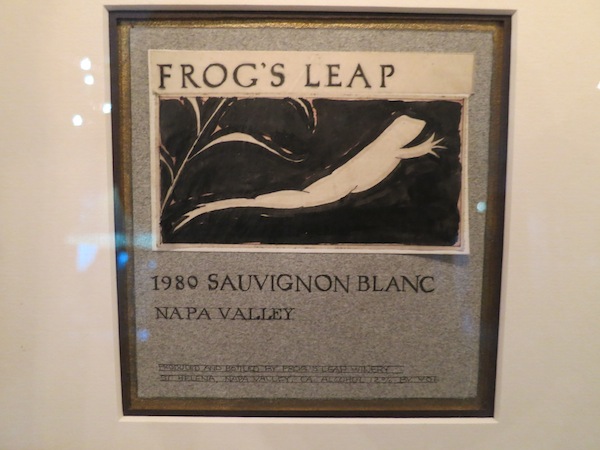

The iconic label

Larry Turley and John Williams pawned their motorcycles, scraped together $10,000, found some second crop Sauvignon Blanc on the spot market, and went to work on their first vintage. Sauvignon Blanc was the perfect choice: quick to ferment and get to bottle, quick to sell, and quick to cash the check. A bit of Zinfandel was also part of that first vintage.

They had a name, Frog’s Leap, combining “Frog farm” (Larry’s property) and “Stag’s Leap” (where John learned his stuff while assisting in the making of the 1973 Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars Cabernet Sauvignon — which went on to win the Judgement of Paris tasting in 1976). But they needed a label.

John put on a suit and tie (both, we assume, borrowed) and went down to San Francisco to meet with the top design firm for wine labels. After several hours of discussion on looks, ideas, images, and what they wanted to convey, the design firm head honcho asked a curious question. “You do understand what it costs to make a wine label, don’t you John?”

“Of course I do!” said John, as he pinched the $300 he brought with him to cover the costs.

“To start the process we’re looking for a $10,000 retainer,” said the honcho. John gulped, and promptly ran back to his motorcycle. On the road back to Napa Valley, he had no idea what to do. Conferring with some friends, he found out the brother of a friend of a friend “is really good at drawing, talk to him. His name is Chuck. He works at the 7-11.”

John rode to the 7-11 and found Chuck, working the counter and drawing pictures on the side. He introduced himself and asked, “Can you make a wine label?”

“Sure I can,” said Chuck, “but I gotta charge you for it.”

John thought about the $300 budget he had for label design. “Well, how much will it be then, Chuck?”

“How ’bout a hundred bucks and two cases of wine?”

(Fast forward thirty years, and Chuck House is now one of the top label designers in the world. Ironically, his retainer is now well above $10,000.)

The original Frog’s Leap label sketch, on display in the tasting room

***

The early days of Organic farming

“I had the whole thing figured out, because I had great people around me,” starts John Williams as he discussed the new vineyard property in eastern Rutherford he purchased after he and his business partner Larry Turley separated. “That vineyard was wonderful because I had wonderful and very nice people telling me what to do. Ironically, they were the same people who sold the chemicals that did what had to be done.”

Over the course of the next few years, the new Frog’s Leap property started showing incredible signs of stress. “They had a chemical for everything, which of course threw the whole thing out of whack. Then another chemical to swing it back the other way. It’s like giving a kid a bunch of caffeine, then some other drug to slow them down. It’s not right, and I saw it. Then I found Amigo Bob.”

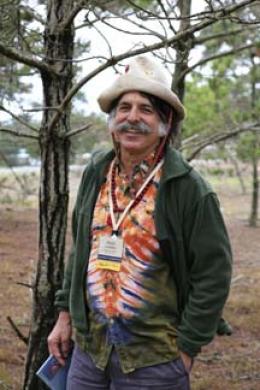

Amigo Bob Cantisano is a legend in California agriculture circles. At the time, he was helping to convert the Fetzer family’s operation in Mendocino to organic practices, and one conversation with him was all it took for John. “I called a meeting with all my growers, and in comes Amigo Bob. Everybody got up and left when they saw this hippie in sandals come strolling in. Turns out he knows more than all of them put together.” (Amigo Bob holds two PhD’s on soil science and agriculture practices.)

Amigo Bob Cantisano is a legend in California agriculture circles. At the time, he was helping to convert the Fetzer family’s operation in Mendocino to organic practices, and one conversation with him was all it took for John. “I called a meeting with all my growers, and in comes Amigo Bob. Everybody got up and left when they saw this hippie in sandals come strolling in. Turns out he knows more than all of them put together.” (Amigo Bob holds two PhD’s on soil science and agriculture practices.)

Amigo Bob put Frog’s Leap on a program goal of soil health, to have a nutrient and life-rich topsoil to help the vine do what it wants to do naturally instead of forcing its hand with chemicals. It’s a long-term process.

“We plant cover crops based on what we want to achieve in three years, not three weeks” says Jonah Beer, Vice President of Frog’s Leap.

The result? Vines that take care of themselves and resist disease naturally, like a healthy human being. Vines that don’t over produce because of some nitrogen being pumped into their system. “Vines that grow like a weed make wines that taste like a weed” John is fond of saying.

The introduction of organic farming in Napa Valley in the 1980’s was seen with suspicion. Nobody was following ‘green’ methods because the chemicals being used were helping to produce bumper crops and thus, profits. Winery after winery in Napa Valley in the 1980’s became dependent of the use of herbicides and pesticides. John in particular would feel the wrath as people chastised him for his ‘unkempt’ vineyards and ‘messy fields’, even though his vineyards were the very first certified organic vineyards in all of Napa Valley.

Over time, though, it became clear that the continued reliance on the herbicides and pesticides was weakening the vineyards throughout Napa. Vines were weakening, but continuously were propped up through fertilizer. With every subsequent vintage, the life energy of the plants became less and less. But John’s vineyards were different. Though messy looking, with a wild growth of cover crops, there was vitality in the soil.

When phylloxera returned to Napa in the 1980’s, the vineyards at Frog’s Leap persevered. The healthy vines actually fought off the phylloxera, and even today they survive. The work that John Williams and Amigo Bob did in the 1980’s is now seen as the gold standard of organic farming in the Napa Valley.

Coming next week:

Part Three — Dry farming, alcohol levels, and what makes Frog’s Leap stand apart.